Annie Contractor, RuralOrganizing.org Education Fund an and Julianne Hopper, Global Health Advocacy Incubator

RuralOrganizing.org polling has shown repeatedly that rural Americans want solutions focused on increasing jobs and wages, decreasing daily expenses, and improving their quality of life, but people with opioid use disorder and their communities face a bleak landscape for a high rural quality of life without a systemic solution to the opioid epidemic.

Rather than the personal vice it is often characterized as, opioid use disorder is a product of pharmaceutical and pharmacy chain corporations’ greed, and the disproportionate impact in rural communities is linked to disinvestment in rural health infrastructure, education, and high quality, affordable housing.

Legislation is needed in the 118th Congress, like the Reentry Act, Due Process Continuity of Care Act, and the Modernizing Opioid Treatment Access Act , which can help plug some of the most glaring gaps in the continuum of care for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment. More policy solutions are needed to address the social distress that drives a cycle of OUD and economic decline. Two promising policy solutions include the Distressed Areas Recompete Pilot Program in its inaugural launch period, and the Rebuild Rural America Act which stands to alleviate economic distress in rural areas disproportionately impacted by opioid use and economic decline.

THE RURAL OPIOID USE DISORDER PROBLEM

Rural Organizing’s Local Progress Reports in 2022 revealed that the opioid crisis is a top-five concern for rural constituents in three rural Ohio counties. The opioid crisis has touched every part of the United States; in 2020, drug overdose deaths increased 31% compared to 2019. Small towns and rural communities have been hit particularly hard; according to 2020 data, the rate of deaths in rural counties was 31% higher than in urban counties of one type of opioid and 13% higher in rural counties for a second subset of opioids (natural and semisynthetic opioids such as morphine and oxycodone). Indeed, 62% of the US counties with the highest rates of OUD are located in rural areas. Factors which are unique to small towns and rural communities both drive OUD and complicate access to treatment.

Drivers of Opioid Use Disorder

Driver 1: Economic Decline

Rural areas across the US have experienced economic decline, leading to higher unemployment rates and poverty. Economic instability can contribute to a sense of despair and hopelessness, higher stress, mental health issues, and social isolation, phenomena which have been linked to opioid use as a coping mechanism.

Driver 2: Disproportionately Higher Rates of Opioid Prescription

Among similar adults, a study found that rural adults are more likely to be prescribed an opioid for their pain than someone in a non-rural area. Historically, rural areas have had higher rates of opioid prescriptions, partly due to a lack of alternative pain management options and limited access to non-opioid treatments. Higher prescription rates increase the availability of opioids in these communities, which can contribute to opioid misuse.

Driver 3: Cultures of Independence and Mental Health Stigma

Research has shown that rural communities may have stronger cultural stigma and negative attitudes towards addiction and mental health issues. Simultaneously, a culture of independence that is uniquely strong in rural communities has been demonstrated in public health research, including as a barrier to medical best practices such as antimicrobial stewardship programs which promote the appropriate use of antibiotics and slow antibiotic resistance. This stigma can create reluctance to seek help, as individuals fear judgment, social ostracization, or professional repercussions. Such attitudes may discourage individuals from seeking timely treatment for OUD.

Treatment Barriers

Despite the higher prevalence of OUD in rural areas, access to treatment and healthcare services is often limited. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reported that individuals living in rural areas were less likely to receive specialized substance abuse treatment compared to those in urban areas.

Treatment Barrier 1: Lack of access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD)

Methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, effective medical treatments for OUD. Methadone is only available for treatment of OUD through federally licensed opioid treatment programs (OTPs), limiting its availability in rural areas, with 88 percent of large rural areas lacking a sufficient number of OTPs. Buprenorphine is available for dispensing at pharmacies; however, recent findings have shown that oftentimes pharmacies do not stock the medication. This issue is prevalent in rural communities, with one study finding many rural pharmacies limited buprenorphine dispensing by refusing to serve new patients or refusing to dispense buprenorphine altogether. A study to understand rural pharmacist’s apprehension to buprenorphine dispensing found that there was a moral objection and mistrust of MOUD, a perceived regulatory limit to dispensing, stigma, and knowledge gaps. This lack of rural access to MOUD which effectively reduces opioid use and overdoses is contributing to rising rates of OUD and overdose deaths.

Treatment Barrier 2: Lack of Alternative Pain Management Treatment Options

While there is growing evidence that opioid alternatives for chronic pain like physical therapy, exercise, psychotherapy, or some combination of these techniques can help reduce the need for opioids, access to these alternatives and to pain management specialists are often limited or non-existent for rural populations. Furthering the challenges with treatment options, rural medical facilities are often lumped together, with vision, dental, medical, and behavioral health services all provided from a single facility, so closures of these rural hospitals, clinics, and other medical providers mean the loss of a host of care and treatment options. Between 2012 and 2018, after rural hospital closures, the average distance to access alcohol and drug treatment increased from 5.5 miles to 44.6 miles in rural areas.

Treatment Barrier 3: Transportation

The lack of reliable public transportation options and long distances to treatment facilities make it difficult for individuals to access healthcare services, attend counseling sessions, and obtain necessary medications like methadone or buprenorphine. The geographical isolation of rural communities exacerbates the difficulties faced by individuals with OUD, hindering their ability to receive timely and comprehensive care. The average estimated drive time for people living in rural areas to their nearest OTP is six times greater than those living in urban areas. Long distances to treatment means that when a person is ready for treatment, has the means to pay for it, and has the information about the service, they may still be unable to get the treatment they need. Further complicating treatment access, some clients may not have driver’s licenses or may have disabilities preventing them from driving, so lack of public transportation services further impede access to ongoing treatment and support groups.

Treatment Barrier 4: Perceived Lack of Confidentiality

A 2019 study found that stigma surrounding addiction prevents individuals from seeking help for substance use disorders (SUDs) in rural communities. Many hold concerns about confidentiality and judgment within small communities, where “everybody knows their neighbors;” even having a car spotted at a mental health provider could be damning. Exacerbating this care gap, rural providers concurrently reported discomfort with screening their patients for substance abuse, a lack of training to do so, and feeling ill-prepared to address screening results and offer treatment. This barrier to treatment can be more evident in rural counties, with one study amongst Ohio physicians showing that bias towards people who misuse opioids was higher amongst rural physicians than urban physicians.

Treatment Barrier 5: Lack of Treatment in Jails and Prisons

Justice-involved populations are disproportionately impacted by SUD, with 65% of incarcerated individuals having an active SUD. However, most individuals who are incarcerated go untreated, with just 12% of jails and prisons offering MOUD. The lack of treatment contributes to high rates of fatal overdose upon reentering society, with findings showing recently released incarcerated individuals to be 40 times likelier to die of a drug overdose during the two weeks following their release than the general population. The severe lack of treatment provided to incarcerated populations can be attributed to the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy (MIEP), which prohibits the use of federal funds and services for medical care for “inmates of a public institution”, regardless of whether they have been convicted. With the cost burden of SUD treatment falling entirely on state and local jails and prisons, often treatment cannot be afforded for incarcerated individuals with opioid use disorder. This issue disproportionately impacts rural populations, as it has been found that people in rural counties are more than twice as likely to go to jail as people in urban areas, and simultaneously there are lower levels of OUD treatment provision in rural jails.

Rural Economic Impacts of Opioid Use Disorder

Substance use disorder is associated with lower labor force participation.

A May 2022 study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates that during the pandemic between 2020-2021, SUD rose more than 20 percent and accounts for between 9 and 26 percent of the decline in labor force participation during this time. The estimate of labor force participation rate (LFPR) of prime-age workers with an OUD is 70 percent, 13 percentage points lower than that of those without an SUD. For people with stimulant use disorder, this rate is even lower, at 67 percent of prime-age workers. Areas of economic distress, correspondingly, are disproportionately rural, including by a measure of low prime-age employment.

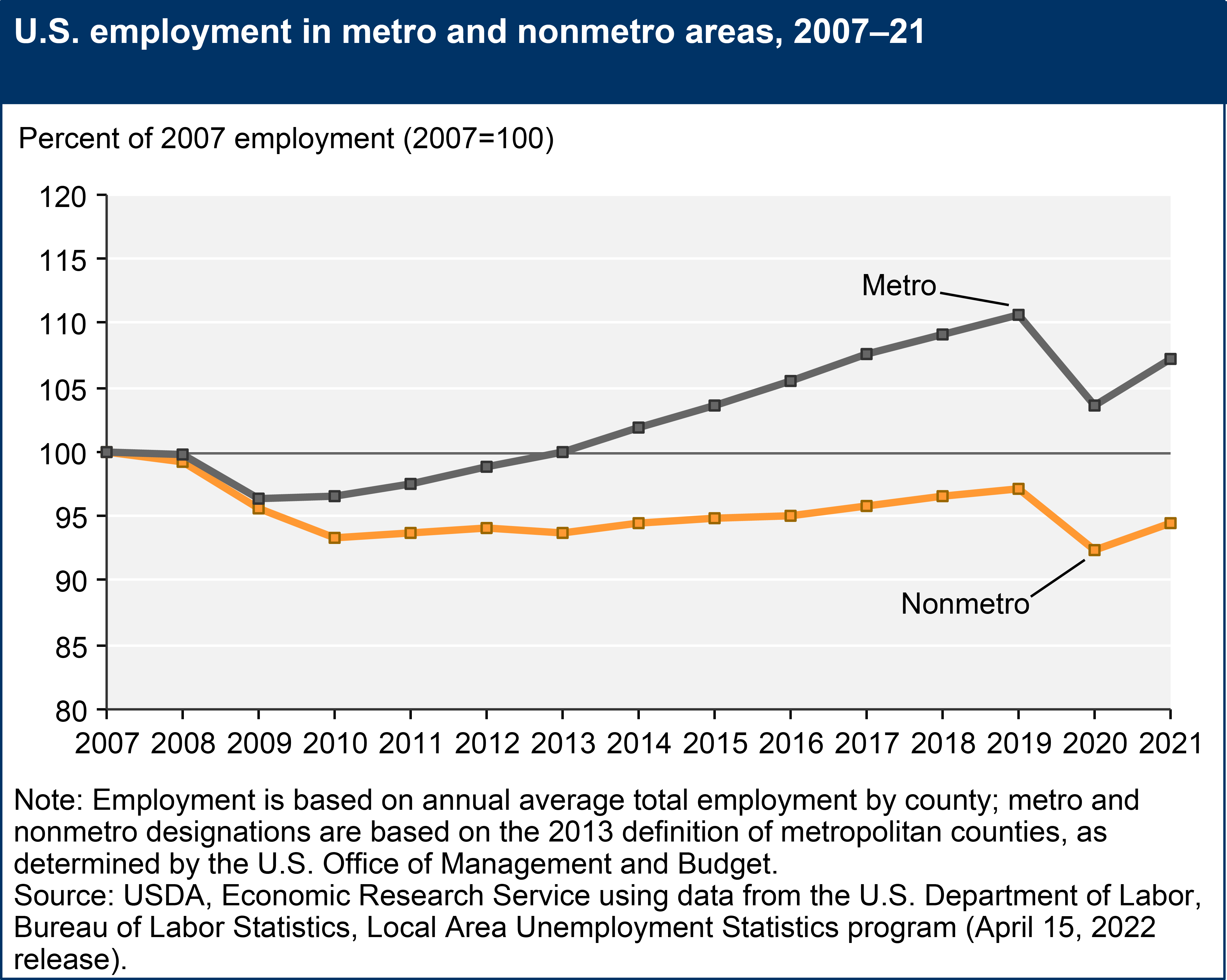

Economic and opioid use disorder are reciprocal challenges, and rural America faces higher impacts of both.

Economic stress is associated with increases in mental illness and substance use. Because rural areas have seen disproportionate declines in economic vitality (see above), this factor has created a reciprocal loop of economic decline fed by SUD, which is in turn fed by economic decline. Exacerbating the challenges, the lack of treatment infrastructure in rural communities means that there are few off-ramps out of this negative economic loop.

“Young adults who stay in economically deprived areas may have a greater accumulation of risk factors for problematic drug use and may be more likely to have established drug dependencies at a young age that cause downward social drift.”

Understanding the Rural–Urban Differences in Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use and Abuse in the United States

Compensation from bad actors is not reaching impacted communities.

In 2022, a master opioid settlement was finalized, dividing $26 billion amongst thousands of communities throughout the United States to assist in their opioid recovery efforts. However, there have been concerns about the lack of transparency about how the funding is being used, and further worries that the funds might not be put to use in a meaningful way (In late June of 2023, opioid settlement payment information was made public. Harm reduction advocates say this access to information is “revolutionary” for the people who care about how the money will be used.). Other concerns have arisen over how funds are being allocated, with rural communities receiving less funding than densely populated urban areas. Johns Hopkins University, which has invested in research to guide the most effective ways to use opioid settlement dollars to recover from the opioid epidemic, indicates that racial disparities in policing and incarceration exacerbate ongoing discrimination along with racial gaps in socioeconomic status, educational attainment, and employment. The Principles for the Use of Funds From the Opioid Litigation recommends investing to tackle root causes of health disparities and eliminate policies with a discriminatory effect.

Structural rural economic factors make opioid use disorder more negatively impactful.

With smaller populations, rural communities often have limited pools of available workers. When a portion of the rural workforce is affected by SUDs, the impact on productivity can be more pronounced due to the smaller size of the labor force. This can lead to a higher proportion of the workforce being affected and a more significant overall economic impact.

Rural areas have higher rates of small businesses (as measured by higher rates of new business starts and higher five-year business survival rates). When employees in small businesses are affected by substance use, the economic consequences can be more directly felt within the community, as the success and viability of these businesses may be at stake.

TREATMENT ACCESS PROVIDES RURAL ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES

With the ongoing overdose crisis, policy responses must be focused upon increasing access to evidence-based treatments that have been proven to save lives. Forced withdrawal from opioids is not an effective way to overcome addiction, as not treating the problem contributes to the cycle of return to use and fatal overdose. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found in a consensus report that MOUD is the “gold standard” of care for opioid use disorder. Despite the effectiveness of MOUD, outdated regulations have placed unnecessary barriers to treatment in place, limiting access to care based on an individual’s geographic location, income level, ability, and race. Increasing access to treatment gives people a greater opportunity for recovery. Current federal legislation has the ability to facilitate wider access to treatment, and should be advocated for passage in the 118th congress as this crisis must be met with immediate action.

- Reentry Act – The Reentry Act would amend the MIEP to permit Medicaid coverage to be reinstated thirty-days prior to release, allowing for treatment initiation while incarcerated and facilitating continuity of care in the community. This is particularly important in rural areas with less funding and treatment infrastructure in place, which has led to lower levels of OUD treatment in rural jails. It has been found that providing treatment in jails and prisons leads to significant reductions in fatal overdose upon release as well as reduced rates of recidivism. A recent study also shows that having Medicaid coverage upon release from correctional facilities increases the likelihood of employment for formerly incarcerated individuals by 25%. By allowing Medicaid benefits to be reinstated prior to release, there will be less economic burden on rural jails and prisons and more incarcerated individuals with opioid use disorder getting the care they need before returning to society.

- Due Process Continuity of Care Act – The Due Process Continuity of Care Act would amend the MIEP by allowing pre-trial incarcerated individuals to receive medical services supported by Medicaid, ensuring that an individual does not lose Medicaid benefits upon arrest. Oftentimes, local jails and prisons do not have the budget or capacity to provide necessary opioid use disorder treatment within their facilities, which can have fatal consequences. It has been found that the fastest growing cause of death in jails and prisons is overdose, and the median time served before a drug or alcohol intoxication death is just one day. This policy is crucial for reducing the cost burden on local carceral facilities while better facilitating access to lifesaving care.

Parallel to the immediate need for evidence-based treatment, policies which aim toward community thriving on both economic and social dimensions are necessary: several explanatory frameworks in the public health literature point to social distress as the upstream driver of OUD. Two leading policies have the potential to drive positive rural social and economic outcomes.

- The Distressed Areas Recompete Pilot Program – The Recompete Pilot Program administered by the Economic Development Administration focuses on economically distressed communities, specifically those where prime-age employment is lagging the national average. Funding can go to any activity that can be credibly linked to improving labor force participation. This flexible funding is revolutionizing economic development by allowing 1) local leaders to design solutions that will truly work for their communities, and 2) enable communities to link related activities into economic revitalization efforts that, under previous federal funding models, would not have been possible. For example, a rural community facing a substance abuse concern may want to invest in a treatment center and its staff, along with a workforce training program that is targeted toward graduates of the treatment program, coupled with subsidized childcare to support those engaging in the treatment and training to be able to attend.

- The Rebuild Rural America Act – The Rebuild Rural America Act addresses long-standing rural barriers to economic thriving through a block grant structure that delivers federal funding to rural communities by formula. By avoiding matching requirements and competitions for tax dollars in which it is structurally harder for rural communities to compete, this bill expands on the innovation of the Recompete Pilot Program and extends flexible economic development funding to every rural community. The Rebuild Rural America act also allocates triple funding to census tracts with high poverty, focusing investment where it is needed most. By making a targeted and sustained effort to invest in holistic community development, this bill can help address the social and economic distress that is clearly linked with OUD and its harms.

RuralOrganizing.org Education Fund is grateful to our partners and coauthors at the Overdose Prevention Initiative for their expertise and contributions to this issue brief.

About the Overdose Prevention Initiative

Established in 2021, the Overdose Prevention Initiative at the Global Health Advocacy Incubator advances policy solutions that save lives and end the U.S. overdose crisis. The Initiative is dedicated to reducing inequities and disparities in substance use disorder care and expanding access to harm reduction services and substance use disorder treatment.